The Python Global Interpreter Lock

December 4, 2018

In CPython, the global interpreter lock, or GIL, is a mutex that protects access to Python objects, preventing multiple threads from executing Python bytecodes at once.

(Source: PythonWiki)

This can be explained more simply, so let me illustrate with an example. Here’s some normal, everyday Python single-threaded code:

def some_func():

# Some code

for _ in range (4):

some_func()We loop 4 times in sequence and execute some_func() each time.

So far, so good.

Now, let’s think up a new function:

def really_really_slow_func():

# Some code

for _ in range(4):

really_really_slow_func()We are now calling really_really_slow_func(). Pretty much the same logic as the previous code snippet, but now we’re doing something slow each time we iterate the loop. Perhaps that really_really_slow_func() is doing something inherently slow, like calculating a unique proof-of-work, so we can’t really do much about making the function itself faster.

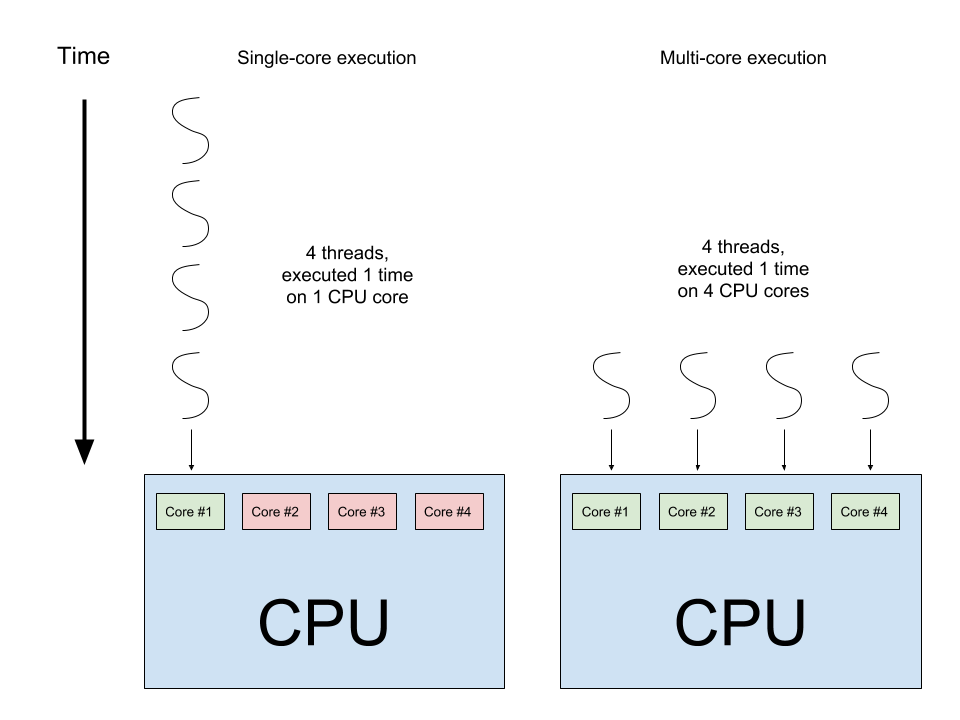

What other options do we have of speeding this up? Well, if we think about it, what’s really happening is that we are calling really_really_slow_func() sequentially in our for loop and thus only allowing one core of our CPU to execute the function in serial 4 times. There are actually 3 other cores of our CPU that are sitting around twiddling their thumbs (assuming our CPU has 4 cores). If we want to speed this code up, we should let the other 3 free CPU cores also run a copy of really_really_slow_func() at the same time. We could potentially achieve this with threads.

Here is an image that illustrates conceptually why executing in parallel threads on different cores is faster:

Let’s do this by assigning each of four threads in a thread pool to run really_really_slow_func(). Ideally, each thread would be scheduled on a different core of the CPU, allowing a 4x speed up of the code (assuming a 4 core CPU).

Here is the code:

import threading

def really_really_slow_func():

# Some code

for _ in range(4):

t = threading.Thread(target=really_really_slow_func())

t.start()However, when we execute this code, we’ll actually see it’s no faster than our previous non-threaded version of the code.

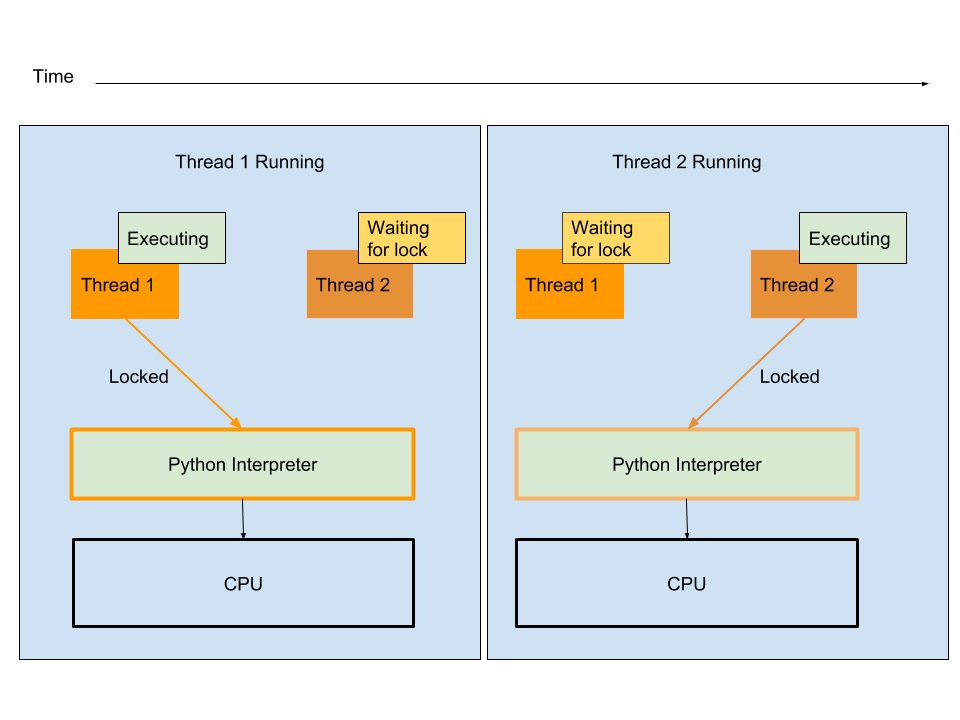

Unfortunately, multi-core execution as illustrated above is not what happens with threads in Python. When you invoke a new thread in your code, the Python interpreter at some point halts the current thread, and runs the new thread you’ve created, instead of running the new thread in parallel on a different core. We end up executing similarly to the single-core setup illustrated above.

The enforcement of a single-threaded execution context is essentially what the Global Interpreter Lock (GIL) was built to achieve. It’s clear that we lose the benefit of threading as a result.

Why does Python do this and not let threads run in parallel?

Python Memory Management

In order to understand why Python behaves this way, we need to understand how Python manages its memory. Obviously, whenever you create a variable in Python, Python needs create it in the computer’s memory. As with all memory-managed languages, Python needs to know when the variable is not needed anymore so it can remove it from memory. Python achieves this by a method called reference counting.

Basically, for every variable that Python stores in memory, it also stores a tally of how many objects are referencing that variable. As long as the reference count for any variable is greater than 0, Python will keep the variable around. When that number hits 0, e.g. no more objects need that variable, the object is removed from memory.

In order for this to work in a threaded environment, the reference counting needs to happen in an orderly manner among all the threads.

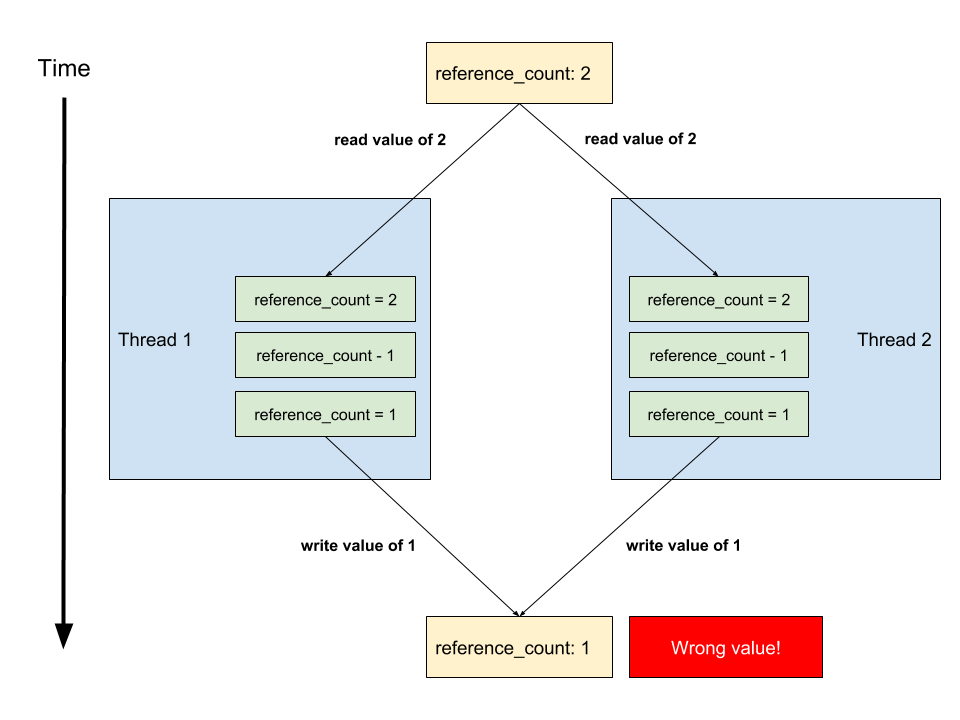

To understand why, we’ll see what happens if threads could modify the reference count simultaneously. Suppose we have two Python threads, Thread 1 and Thread 2, that both reference a variable v. The reference count for v would then be 2.

Then, suppose both threads simultaneously remove their reference to v. Well, as we just specified, at the time they both remove their reference, v’s reference count is 2. If each thread read the reference count simultaneously, each thread would get an initial reference count of 2 for v. Each thread would then decrement the reference count value of 2 by 1. The final reference count as calculated by each thread would then be 1. Unfortunately, the actual reference count should actually be 0, since both threads removed their reference to v.

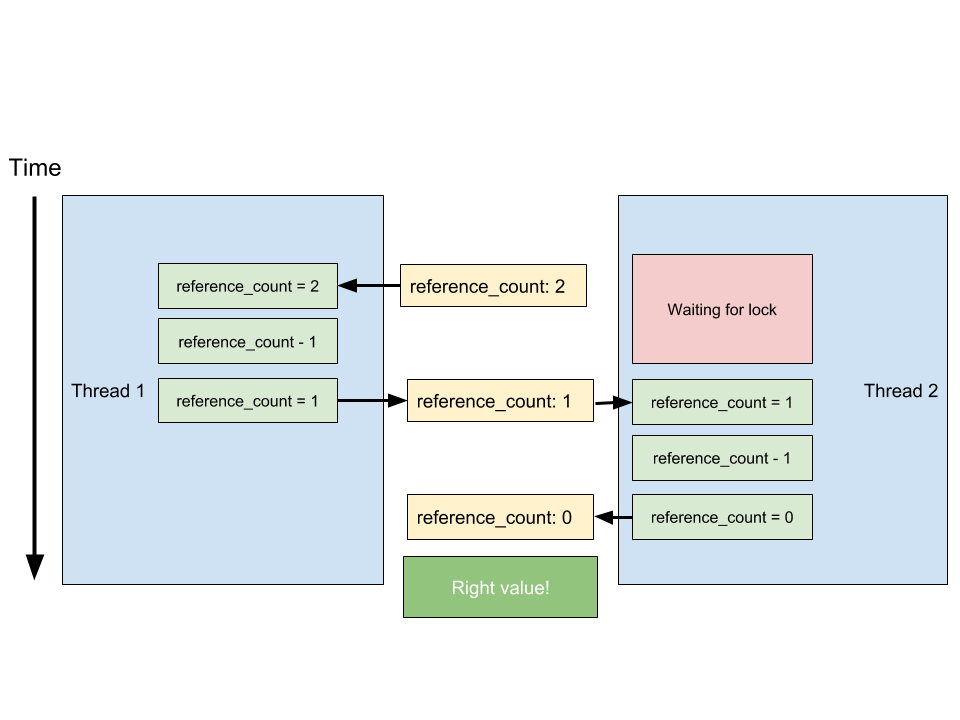

Locking

In order to remedy it, we could make sure that both Thread 1 and Thread 2 can’t modify the reference count simultaneously. We achieve this by locking the reference count so that Thread 2 waits while Thread 1 reads and decrements the reference count, and only then do we allow Thread 2 to decrement the reference count in turn.

This implementation was actually tried out in Python in the early days. However, locking the reference count for every increment or decrement for every object over every thread proved to be extremely slow. The faster solution is to just lock the entire Python interpreter and let only one thread run on the interpreter at any given time. Hence, the Global Interpreter Lock:

The GIL is certainly faster than individual reference count locks, but it still allows only a single thread to execute. There has been a lot of work to improve the way in which Python schedules threads, and there is a definite improvement in Python 3 over Python 2 in that regard. However, true parallelism via threads has not yet been achieved. That can only happen by removing the GIL altogether.

Lock-free programming and Python

As we’ve seen, the reference counting issue is, in large part, the reason for the GIL.

Recently, I’ve been reading about lock-free programming, and particularly compare-and-swap. In this algorithm, the code will read some key memory location and remember the old value. Based on that old value, it will compute some new value. Then it will swap in the new value, making sure the memory location is still equal to the old value before it swaps in the new value.

Essentially, this algorithm makes sure no other code modified the original value in the time it took to modify that value. If the value was modified, it will attempt to repeat the process until it’s able to successfully swap in the new value.

You may see how it could apply to our locking problem and reference counting. Instead of locking the reference count, we could merely apply our compare-and-swap algorithm. A thread would try and modify the reference count and swap it in, so long as the original reference count was not changed. If the original reference count was modified (by another thread), it’ll attempt to redo the entire operation with the new value.

Although this might prevent the overhead of acquiring a lock every time we wanted to modify the reference count, it does create other issues. For example, a thread might be repeatedly attempting to decrement a reference count, but cannot, as other threads are continuously modifying the original count themselves. This would lead the original thread being stuck in a compare-and-swap loop for a long while.

Conclusion

As we have seen, there is good reason why the Python interpreter runs only a single thread at a time. If we want real parallelism, we should stick with running multiple processes instead of multiple threads. That can be achieved with the concurrency module in Python. However, that’s the subject of a whole ‘nother blog post!